INTRODUCTION

Low back pain (LBP) is a condition characterized by pain and discomfort localized beneath the ribcage and above the gluteal folds, often with potential radiation to the legs1. The World Health Organization classifies LBP based on its cause and duration, with the causes being 1) non-specific, 2) LBP with nerve root involvement, and 3) LBP due to major pathology (e.g., cancer, fracture), and the duration being acute (lasting less than six weeks), subacute (lasting 6–12 weeks), or chronic (exceeding 12 weeks)2.

Approximately 90% of lumbar spine-related discomfort has been attributed to non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) This condition is commonly the result of mechanical overuse and dysfunction of the spine and surrounding structures, including the core muscles3. Contributing factors often include unhealthy habits such as improper sitting, incorrect bending and lifting techniques, and poor posture. Mechanical LBP particularly characterized by pain that intensifies with movement and subsides during rest4.

In Egypt, 99.5% of physical therapists (PTs) report work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs), with the lower back being the most commonly affected area, accounting for 69.1% of cases. Female PTs are more likely to have WMSDs compared to their male counterparts4.

Chronic LBP can lead to alterations in lung capacity and diaphragm mechanics, both of which are critical for stabilizing the lower back. The primary stabilizers of the lower back, viz. the diaphragm, transverse abdominis (TrA), multifidus, and pelvic floor muscles, collaborate to promote postural and torso stability. Individuals with LBP often demonstrate delayed activation of the TrA and multifidus muscles, as well as restricted diaphragm movement, leading to insufficient intra-abdominal pressure (IAP)5. Furthermore, chronic LBP is associated with atrophy of the multifidus muscle, which is often compensated for by the erector spinae muscles6. This compensation, along with the weakened TrA muscle, increases the compressive forces on the spine, exacerbating LBP7.

It is essential to evaluate the respiratory and postural functions of the diaphragm to improve the assessment and management of LBP. Ultrasonography can be employed to assess variations in diaphragm thickness and excursion8. Additionally, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) serve as a valuable tool in evaluating the functional state of the diaphragm and overall respiratory system performance9,10.

Lumbar spine movement can be efficiently gauged by utilizing an air-filled reservoir known as a pressure biofeedback unit (PBU)1. The pressure biofeedback can guide core stabilization exercises focused on engaging the diaphragm, TrA, and other core muscles while maintaining a neutral lumbopelvic position, thereby promoting spinal stability11.

One manual intervention that can indirectly elongate tight diaphragmatic muscle fibers, enhancing more efficacious diaphragmatic contractions and improving pulmonary function, is the diaphragmatic release technique12.

Therefore, we aimed to compare the effects of core stability exercises and diaphragmatic release techniques on respiratory functions in PTs having chronic LBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This randomized controlled trial was authorized through the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University (P.T.REC/012/004373). All participants signed informed consent pre-trial. This trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05860283) and followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted at the outpatient clinic of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University. A total of ninety female PTs employed at Kasr-Al-Ainy Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, with chronic mechanical LBP were recruited. The inclusion criteria were as follows: participants aged 25–35 years, a body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m², a history of mechanical LBP persisting for at least six months with a minimum of three episodes of LBP, an Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score ≥ 7, and no regular participation in any training program or manual therapy intervention during the preceding six months.

Exclusion criteria included current or former smokers, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m², a history of acute traumatic LBP within the past two months, lumbar, abdominal, or gynaecological surgery within the past year, disc herniation or spinal fracture, radiating pain to the leg, neurological, respiratory, or cardiovascular pathologies, infectious health conditions, current menstruation (no evaluations or sessions were conducted during menses), pregnancy, or postpartum status.

Sample size calculation

The minimum required sample size was calculated using G-power 3.1.9.2 software. With a power of 90%, significance level of 5% and 95% confidence interval, power calculation was performed using data obtained from Baxi et al.13 The effect size was f = 0.41347. Therefore, 78 was the minimum number of subjects required in this study; however, the recruited sample size was expanded to demonstrate the effectiveness of the study, yield suitable outcomes and account for the expected dropout rate.

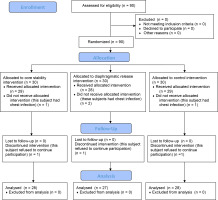

Participants were equally assigned to three groups at random using permuted block randomization Group A (Core Stability Exercise), Group B (Manual Diaphragmatic Release), and Group C (Control). Each participant was familiarized with the objectives, equipment, and procedures of the study within their specific group; however, they were blinded to the procedures in the other groups. Each participant received treatment sessions three days per week over six weeks (Figure 1).

Primary outcome

Pulmonary function test

The PFTs were performed using a well-calibrated spirometer (Jaeger Vyntus™ spirometer) to evaluate lung volumes and capacities. Participants were asked to take three regular breaths, followed by a quick and deep inhalation. They then forcefully exhaled for 6 s to assess Forced Vital Capacity (FVC), Forced Expiratory Volume in one second (FEV1), Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF), and the FVC/FEV1 ratio14. Participants were required to inhale and exhale as quickly and deeply as possible for 12 s to measure Maximum Voluntary Ventilation (MVV)15. The highest values from three test runs were recorded14.

Diaphragm excursion and thickness

Diaphragm excursion and thickness were evaluated according to Ziaeifar et al.8 via a high-resolution real-time ultrasound apparatus (Sony 1-7-1 Konan Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan). To minimize possible bias, the measurements were performed by an experienced radiologist who was blinded to the group assignments. Diaphragm excursion and thickness were determined using M-mode and B-mode ultrasound, respectively. In this study, measurements were taken exclusively from the right hemidiaphragm.

For diaphragm excursion, a 3.5 MHz curvilinear transducer was positioned on the lower intercostal region of the right hemidiaphragm between the anterior axillary and midclavicular lines, oriented medially, cranially, and dorsally to obtain the optimal view during quiet breathing (QB) and deep breathing (DB).

Diaphragm thickness was measured using a 7.5 MHz linear transducer placed between the eighth and tenth intercostal spaces. Measurements were taken at the end of inspiration (Tins) and expiration (Texp) during DB.

Secondary outcome

Oswestry disability index for pain-related disability

The ODI is a medical evaluation questionnaire comprising ten categories used to quantify disability related to LBP and provide a percentage score. Each category is scored from 0 to 5. The final score was calculated according to Ozkaraoglu et al.16 A 100% score indicates complete disability (bed dependency), while a 0% score indicates minimal impairment.

Treatment Procedures

Core stability exercise (Group A)

This group received core stability exercises via PBU. The participants were provided with visual, auditory, and tactile biofeedback during the sessions. They were instructed to monitor the pressure gauge and avoid any compensatory movements or breath-holding1.

Participants began the exercises in a crooked lying position with the inflated chamber of the PBU placed at the L4-5 level. The exercise regimen started with the patient performing an abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre (ADIM) from this position; this was gradually increased in difficulty over the six weeks by the patient incorporating different leg movements while maintaining the ADIM17. Participants who experienced pain and were unable to complete the exercises were retrained until they could perform them correctly. Each session lasted 20 min18, with three sets of ten repetitions each19.

Manual diaphragmatic release (Group B)

This group received the manual diaphragmatic release technique. While lying in a supine position, the practitioner applied pressure on the inner side of the 7th to 10th rib costal cartilages, gradually deepening the pressure with each respiratory cycle. This procedure was conducted three days/week/six weeks, with each session lasting 45 min20. Each session consisted of 4 sets of 5 deep breaths per set, with a two-minute rest between sets12.

Traditional physical therapy (Group C Control)

All participants in all groups received the following outdated physical therapy techniques: (1) Therapeutic Ultrasound (US): Ultrasound was applied to the lumbar paravertebral muscles using a continuous mode with an intensity of 1.5 W/cm² and a frequency of 1 MHz. The ultrasound was delivered with a 5 cm² transducer head for six minutes; (2) Hot Pack: A hot pack was applied to the lower back area for 20 min; (3) Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS): TENS was administered to the lower back for 20 min, with a frequency of 110 Hz and an amplitude of 15 mA for 100 ms21. Ultrasound and TENS were applied using a Phyaction CL (Uniphy, serial no. 70408, Belgium) device.

Statistical analysis

The recorded data were determined utilizing the SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Normally-distributed variables (parametric data) are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and ranges, while non-normally distributed variables (non-parametric data) are reported as median with interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative variables were summarized as numbers and percentages. The normality of the data distribution was assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

The findings revealed no significant variance in age (p = 0.413) and BMI (p = 0.386) among the groups (Table 1).

Table 1

Subject characteristics

Intergroup comparison of primary and secondary outcomes pre-intervention

The results indicate that there were no significant variances in both primary outcomes: FVC (p = 0.114), FEV1 (p = 0.297), FEV1/FVC Ratio (p = 0.617), PEF (p = 0.112), MVV (p = 0.659), Diaphragmatic Excursion during QB (p = 0.172), Diaphragmatic Excursion during DB (p = 0.112), and Diaphragm Thickness Change (p = 0.098) as well as secondary outcomes: ODI (p = 0.334) (Table 2).

Table 2

Intergroup comparison regarding primary and secondary outcomes pre-intervention.

Comparison of PFT among groups pre- and post-treatment

The results indicate that both the Core Stability and Diaphragmatic Release groups experienced significant improvements in pulmonary function measures (FVC (p = 0.001), FEV1 (p = 0.001), PEF (p = 0.001), and MVV (p = 0.001) post-treatment compared to the Control Group. No significant variations in the FEV1/FVC ratio were noted between the groups, either pre- or post-treatment (Table 3).

Table 3

Comparison of PFT among groups pre- and post-treatment

| Pulmonary function tests | Core stability Group | Diaphragmatic Release Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| FVC (Litres) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 3.42 ± 0.37 | 4.46 ± 0.53A | 3.03 ± 0.36 | 4.14 ± 0.35A | 3.37 ± 0.29 | 3.40 ± 0.30B |

| Range | 2.69-4.3 | 3-5.82 | 2.39-4.1 | 3.52-5 | 3-4.12 | 3.02-4.16 |

| Change | 1.04 ± 0.24 (0.31-1.52)A | 1.10 ± 0.16 (0.87-1.48)A | 0.04 ± 0.02 (0-0.12)B | |||

| T-test | -22.917 | -36.633 | -1.440 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.568 | |||

| FEV1 (Litres) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.91 ± 0.24 | 3.79 ± 0.35A | 2.60 ± 0.34 | 3.52 ± 0.29A | 2.83 ± 0.25 | 2.86 ± 0.25B |

| Range | 2.45-3.29 | 2.84-4.5 | 2.06-3.36 | 3.05-4.13 | 2.41-3.6 | 2.43-3.62 |

| Change | 0.89 ± 0.20 (0.26-1.22)A | 0.92 ± 0.13(0.58-1.14)A | 0.03 ± 0.02 (0-0.09)B | |||

| T-test | -23.777 | -36.620 | -0.755 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.291 | |||

| FEV1/ FVC (%) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 85.40 ± 4.40 | 85.41 ± 4.01 | 84.96 ± 4.55 | 85.26 ± 4.08 | 84.21 ± 4.73 | 84.27 ± 4.68 |

| Range | 76.3-95.9 | 77.31-94.7 | 76.79-94.31 | 77.54-94.6 | 78.14-94.04 | 77.74-93.93 |

| Change | 0.01 ± 0.01 (-1.2-1.5) | 0.30 ± 0.16 (-1-6.31) | 0.06 ± 0.02 (-0.74-0.87) | |||

| T-test | -0.086 | -1.146 | -0.828 | |||

| P-value | 0.932 | 0.262 | 0.415 | |||

| PEF (Litres/ min) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.20 ± 0.83 | 7.01 ± 0.87A | 4.79 ± 0.92 | 6.72 ± 0.93A | 5.57 ± 0.86 | 5.60 ± 0.84B |

| Range | 3.6-7.83 | 5.11-8.28 | 3.07-6.31 | 5.42-8.04 | 3.11-7.54 | 3.31-7.57 |

| Change | 1.81 ± 0.47 (0.28-2.97)A | 1.93 ± 0.50 (1.2-3.01)A | 0.04 ± 0.01 (-0.23-0.43)B | |||

| T-test | -14.039 | -20.931 | -1.675 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.105 | |||

| MVV (Litres/ min) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 75.49 ± 11.35 | 99.24 ± 12.18A | 73.96 ± 14.40 | 96.76 ± 15.96A | 72.46 ± 11.32 | 73.03 ±11.41B |

| Range | 54.9-97.1 | 73.2-120 | 45.1-97.8 | 63.8-135.9 | 46.8-89.1 | 47.1-90.9 |

| Change | 23.75 ± 6.17 (15.6-34.4)A | 22.80 ± 5.93(5.8-38.1)A | 0.57 ± 0.15 (0.2-2.2)B | |||

| T-test | -22.911 | -19.157 | -0.613 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.382 | |||

FVC- forced vital capacity, FEV1- forced expiratory volume in 1st second, MVV- maximum voluntary ventilation, p-value- probability value, PEF- peak expiratory flow, SD- standard deviation, T- test- test value. Different capital letters indicate significant variation at (p<0.05) among means in the same row.

Comparison of diaphragmatic ultrasound among groups pre- and post-treatment

The results indicate that both the Core Stability and Diaphragmatic Release groups experienced significant improvements in diaphragmatic excursion and thickness post-treatment (p = 0.001), with the Diaphragmatic Release Group showing the most pronounced improvement in excursion, and the Core Stability Group demonstrating the greatest increase in diaphragm thickness (p = 0.001). The Control Group exhibited no significant changes in any of the measured outcomes (Table 4).

Table 4

Comparison of diaphragmatic ultrasound among groups pre- and post-treatment

| Diaphragmatic Ultrasound | Core stability Group | Diaphragmatic Release Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Excursion QB (cm) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 0.79 ± 0.50 | 1.73 ± 0.63B | 0.81 ± 0.32 | 2.55 ± 0.48A | 1.30 ± 0.79 | 1.32 ± 0.78C |

| Range | 0.12-2.06 | 0.63-3.1 | 0.12-1.3 | 1.84-3.43 | 0.17-3.1 | 0.18-3.1 |

| Change | 0.94 ± 0.24 (0.24-1.72)B | 1.74 ± 0.45 (1.16-2.3)A | 0.02 ± 0.01 (-0.13-0.21)C | |||

| T-test | -12.222 | -28.167 | -1.933 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.064 | |||

| Excursion DB (cm) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 2.58 ± 0.64 | 3.71 ± 0.71B | 2.27 ± 0.93 | 4.88 ± 1.14A | 2.83 ± 0.82 | 2.92 ± 0.88C |

| Range | 1.26-4.15 | 2.42-5.36 | 0.58-4.57 | 3.44-8.52 | 1.23-4.5 | 1.26-4.93 |

| Change | 1.13 ± 0.29 (0.19-1.94)B | 2.62 ± 0.68 (1.36-3.95)A | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.01-0.76)C | |||

| T-test | -19.026 | -22.779 | -0.286 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.282 | |||

| Diaphragm thickness change (%) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD | 57.37 ± 24.03 | 254.11 ± 15.83A | 58.67 ± 22.82 | 157.01 ± 30.65B | 53.43 ± 17.32 | 54.86 ± 17.46C |

| Range | 20-95.45 | 215.39-287.5 | 20-86.36 | 100-192.86 | 20-85.71 | 21-86.21 |

| Change | 196.74 ± 51.15 (154.27-237.14)A | 98.34 ± 25.57 (32.54-162.5)B | 1.43 ± 0.37 (0-2.38)C | |||

| T-test | -43.586 | -16.307 | -1.728 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.171 | |||

Comparison of ODI among groups pre- and post-treatment

These results indicate that both the Core Stability and Diaphragmatic Release interventions significantly improved disability outcomes (p = 0.001), as measured by the ODI, in comparison to the Control Group, with the Control Group showing a smaller, yet still significant, improvement.

Table 5

Comparison of ODI among groups pre- and post-treatment

| ODI% | Core stability Group | Diaphragmatic Release Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Mean ± SD | 21.71 ± 10.62 | 4.86 ± 3.59B | 20.00 ± 5.17 | 4.93 ± 2.67B | 23.36 ± 8.22 | 15.79 ± 6.14A |

| Range | 12-52 | 2-14 | 10-36 | 1-10 | 12-38 | 6-26 |

| Change | -16.86 ± 4.38 (-40--8)B | -15.07 ± 3.92 (-26--8)B | -7.57 ± 1.97 (-14--4)A | |||

| T-test | 10.988 | 18.584 | 2.229 | |||

| P-value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.024 | |||

DISCUSSION

Our aim was to compare the effects of core stability exercises and diaphragmatic release techniques on respiratory functions in 83 female PTs with chronic LBP.

Core stability exercises are prepared to restore or enhance the ability of the neuromuscular system to control and protect the spine from injury or reinjury17. In this study, six weeks of core stability exercises resulted in significant improvements in PFTs. These findings are consistent with Mohan et al.22, who reported a significant elevation in MVV after core muscle training, and Lalnunmawii et al.23, who observed significant ameliorations in FEV1, FVC, and PEF after six weeks of core stability training in healthy subjects. However, our FEV1 and FVC findings contrast with those of Oh et al.24, who found no significant changes after four weeks of abdominal drawing-in manoeuvre lumbar stabilization exercises in women with LBP, possibly due to the shorter duration of their intervention.

The abdominal muscles govern almost 20% of respiratory activities by facilitating forcible and prolonged expiration. Consequently, as the intra-abdominal pressure increases during lumbar stabilization exercises, the diaphragm is forced into the thoracic cage by the abdominal muscles, contributing to the increase in volume and pace of exhalation reflected in PFT13.

The significant increase in diaphragm thickness found in this study agrees with the results of Oh et al.24, who also observed raised diaphragm thickness after ADIM lumbar stabilization exercises in women with LBP. People with CLBP experience increased diaphragmatic weakness. Since the diaphragm is crucial to the stability of the spine, its thickness is enhanced by stabilization exercises25.This is explained by the overloading principle; the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles react to training stimuli by changing their structural makeup and increasing in size26.

The significant increase in diaphragm excursion observed in our study is supported by the outcomes of Kolar et al.27 and Sembera et al.28, who demonstrated that diaphragm excursions increase during postural activities involving the upper and lower limbs and are unaffected by voluntary abdominal contraction. Since the diaphragm serves both postural and respiratory functions, its position and excursion increase while breathing in postural loading settings29.

The ODI improvement in our study is consistent with the outcomes reported by Shah et al.6, who recognized significant ODI improvements in subjects who received core stability exercises combined with diaphragmatic breathing, similar to the intervention used in our present study with the PBU. Abdominal and lumbar stabilizer muscle weakness contributes to LBP by failing to provide lumbar support, which puts considerable loads on the spine25. This suggests that core stability exercises progressively increase the length tension relationship of the core muscles, leading to better tensile strength and pain reduction13.

Manual diaphragmatic release is a technique that alleviates diaphragmatic adhesions and elongates the insertional band of the anterior costal fibres of the diaphragm during deep and slow breathing, allowing for more efficient diaphragm mobility and chest flexibility12.

In this study, six weeks of diaphragmatic release also led to significant improvements in PFTs. These results align with the findings of Rutka et al.30, who found significant improvements in FVC and FEV1 after diaphragmatic release in children with cerebral palsy, and Thali and Ganesh31, who observed a significant increase in PEF after applying various manual diaphragmatic techniques in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The reduced diaphragm excursion in chronic LBP subjects is known to decrease all PFT measures, including MVV32, making the significant improvement in MVV observed in our study likely attributable to the increased diaphragmatic excursion.

However, our results contrast with those of Ali and Duruturk33, who found no improvements in FVC, FEV1, or MVV after applying manual diaphragmatic release in obese individuals.

The significant increase in diaphragm excursion observed in our study is consistent with Elnaggar et al.12, who reported increased diaphragm mobility in asthmatic patients following diaphragmatic release. Similarly, Bennett et al.34 found improvements in diaphragm mobility after applying diaphragm stretching in children with cerebral palsy. Our study demonstrated a significant elevation in diaphragm thickness which matched the results of Inyoung35. In that study, diaphragm thickness and excursion increased in individuals having LBP and treated with diaphragm stretching. In contrast, studies by Mancini et al.36 and Fernandez-Lopez et al.37 did not find changes in diaphragm thickness after a single session of manual therapy, likely due to the short duration of the intervention.

By manually lengthening the restricted diaphragmatic muscle fibres by pressing on its anterior attachments, diaphragmatic contraction is facilitated through the length-tension relationship38. This has been found to result in improved chest expansion38 and expiration potential, which affects the PFT. It has also been observed to improve diaphragm excursion31, thickness and contraction rate35.

The observed improvement in ODI in our study is consistent with Martí-Salvador et al. 39 and Fernandez-Lopez et al.37, who demonstrated significant improvements in lumbar pain and disability after applying various diaphragmatic relaxation techniques. The significant reduction in pain noted after diaphragmatic release may be attributed to the activation of the vagus nerve during this manoeuvre40. It is likely that this may create parasympathetic effects that relax the spasmed back muscles, reducing the LBP.

In the inter-group comparison, the core stability group demonstrated a more significant change in diaphragm thickness, while the diaphragmatic release group exhibited a more significant change in diaphragm excursion. This is the first such comparison of these variables using the same study groups. We speculate that the significant variation in excursion between the groups may be due to the deep grip applied at the inner costal margin in the diaphragmatic release group; this likely facilitated greater excursion than in the core stability group, where no external manoeuvres were applied to stretch or elongate the diaphragm.

Conversely, the significant variance in thickness increase between the groups could be due to the greater challenge placed on the diaphragm in the core stability group. This group required the diaphragm to balance its dual postural-respiratory role during lower extremity movements, whereas the diaphragmatic release group did not impose additional challenges on the diaphragm as the patients’ limbs were relaxed. The increased demand on the diaphragm in the core stability group likely resulted in a greater elevation in thickness compared to the diaphragmatic release group.

Further long-term studies including electromyography (EMG) are recommended to identify changes in muscle activation patterns between core stability exercises and diaphragmatic release. Moreover, future studies may also investigate the effect of core muscle training with PBU on maximum inspiratory and expiratory pressures.

CONCLUSIONS

Since diaphragm thickness showed better improvement in Group A, while diaphragm excursion showed better improvement in Group B, therefore, combining both core stability training and manual diaphragmatic release would be an efficient method for enhancing respiratory and ultrasound variables, as well as reducing functional pain in subjects with chronic LBP. It is therefore recommended to combine both therapeutic manoeuvres in the management of chronic LBP to maximize benefits related to respiratory functions, pain relief, and functional performance.