INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 is a highly-contagious disease brought on by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1. COVID-19 patients may present to hospital with a spectrum of symptoms ranging from asymptomatic, mild upper respiratory symptoms to severe pneumonia and multiple organ failure. While some patients are followed up in the hospital ward, those with a mild course recover without hospitalization. Although some of the symptoms disappear after the illness, others ranging from fatigue to respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath, sleep disturbance and coughing can persist1-3.This is not only a problem for patients but also a serious public health issue. The duration and severity of post-acute COVID-19 is currently unclear, with a variety of nomenclatures being used to describe it, such as Post COVID-19, Chronic COVID-19, Long COVID-19 or Post-Acute COVID-19. The WHO defines long-term symptoms as Post COVID-194.

Although it has been stated that Post COVID-19 is more common in people who have had severe COVID-19 disease, its symptoms may also occur in patients who have only experienced mild symptoms or an asymptomatic course5. One of the most common acute and post-COVID-19 symptoms, associated with shortness of breath and fatigue, is reported to be respiratory muscle dysfunction. Farr et al.6 observed impaired diaphragm contractility in 76% of survivors of severe COVID-19. A case report by Van Steveninck and Imming7 reported diaphragmatic dysfunction (decreased diaphragm thickness and thickened fraction) in a severe COVID-19 patient before intubation and respiratory failure became evident. Furthermore, studies have reported that patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 have abnormal lung function and decreased physical performance (6DYT) even after recovery8-11. Therefore, evaluation of respiratory muscle function is important for planning an effective treatment program. Most research on the effects of COVID-19 on inspiratory muscles indicate a weakening of these muscles; however, most of this research has included individuals with severe disease6,12.

Apart from fatigue, dyspnea, respiratory problems and other clinical manifestations, sleep disturbances are also commonly reported after ‘COVID 19’13. Studies have shown that a significant proportion of COVID-19 patients experience significant sleep disturbances, as well as psychological distress such as depression, anxiety and traumatic stress14,15. In addition, infection and hospitalization have been associated with lower absolute lymphocyte counts, higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios, acute respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, pre-existing mental health conditions, and an increased risk of sleep disturbance for longer hospital stays16. However, no study has investigated sleep problems in patients with COVID-19 with a mild course of the disease who were not hospitalized.

Most of the long-term follow-up studies of COVID-19 have involved hospitalized patients. Most infected young people were found to have milder illness without hospitalization. Most studies investigating respiratory muscle involvement, fatigue, exercise capacity and other long-term outcomes have been performed with hospitalized patients. In contrast, few studies have investigated the effect of mild COVID-19 on symptoms such as fatigue, respiratory functions and deconditioning among outpatients17.

The purpose of our study is to compare the respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity, and sleep quality between young individuals who contracted COVID-19 and recovered without the need for hospitalization, indicated by a negative COVID-19 test, and a group who had never contracted COVID-19.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This case-control study was conducted between February 2023 and October 2023. The study was approved by the non-interventional ethics committee of Kırıkkale University (decision no: 2022.12.07; date: 11.01.2023). Informed consent was provided by each participant in the study. The Declaration of Helsinki was followed in the conduct of the study. This trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (registration no: NCT06008470).

The study group included sedentary individuals between the ages of 18-45, studying at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Kırıkkale University. The inclusion criteria included a negative PCR test result three months after confirmed infection, not being hospitalized during the disease, non-smokers, not involved in any exercise program, no symptoms of acute illness, such as those associated with upper or lower respiratory tract infection, and willingness to participate.

The control healthy group included individuals aged 18-45 years, with no history of COVID-19 infection, no known chronic disease such as cardiopulmonary disease, and non-smokers. Evaluations were conducted at the Department of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation, Kırıkkale University.

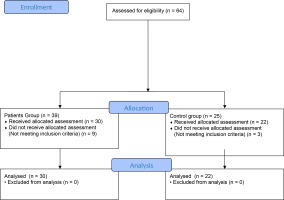

The exclusion criteria comprised professional athletes, patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of COVID-19, patients diagnosed with signs and symptoms of respiratory diseases such as bronchial asthma, COPD or tuberculosis, and those with musculoskeletal, cardiac, metabolic and other systemic problems that may affect physical activity. The flow diagram of participants according to CONSORT is given in Figure 1.

The socio-demographic characteristics (age, height, body weight, body mass index, exercise and smoking habits, COVID-19 history, COVID-19 vaccination status) of all individuals were recorded. In addition, pulmonary function was evaluated with a spirometer, respiratory muscle strength with an electronic mouth pressure measuring device, exercise capacity with a six- minute walk test (6MWT), and sleep quality with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Scale. All assessments were performed by the same physiotherapist.

Evaluations

Pulmonary function test

Pulmonary function test measurements were performed with a spirometer (BTL-08 Spiro Pro system, Germany) according to the ATS criteria. Three consecutive measurements were made and the best one was recorded. Following pulmonary function testing, values for forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and peak expiratory flow (PEF) were measured in liters18.

Inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength

Maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) and maximal expiratory pressure (MEP) were measured using an electronic mouth pressure monitor (Pocket-Spiro MPM 100 M, Bruxelles). MIP was tested at residual volume, whereas MEP was evaluated at total lung capacity. Three measurements were taken, with the best measurement being noted. The subject was instructed to perform a maximal expiration during the MIP measurement. After that, the airway was sealed with a valve, and the subject was instructed to execute maximal inspiration and hold it for one to three seconds. The subject was instructed to perform maximal inspiration for one to three seconds against a closed airway, followed by maximal expiration. Out of the three measurements, the best one is chosen. The two best measured readings were checked to make sure the discrepancy was no greater than 10% or 5 cmH2 O. Age and sex-specific MIP and MEP values are within normal ranges. The individual’s MIP and MEP values were compared with the reference formulae given by Evans et al.19.

Six-minute walk test

The 6MWT was performed to evaluate the participants’ functional exercise capacity was evaluated according to American Thoracic Society’s recommendations. The participants were instructed to walk as far as possible down a 30-meter hallway for six minutes at their own pace. Throughout the test, people were free to pause and take breaks as needed. The test was administered twice every other day. The maximum walking distance in six minutes was expressed in meters. In addition, the 6MWT distances reached by the individuals were calculated as a percentage of reference values for healthy adults of the same sex, age and height20.

Sleep Quality

Sleep quality was measured with a Turkish version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), developed by Buysse et al.21. It is a self-report measure used to evaluate sleep disruption and quality over the previous month. It comprises 24 questions in total: 19 self-report, and five answered by a partner or roommate. Its eighteen scored questions are divided into seven parts. (Subjective Sleep Quality, Sleep Latency, Sleep Duration, Habitual Sleep Efficacy, Sleep Disorder, Sleep Medication Use and Daytime Dysfunction). Each component is assessed on a 0–3 point scale. The scores for each of the seven components are summed to give an overall score, with a score of five or above indicating “poor sleep quality” on a scale of 0 to 21. The Turkish language version of the scale has demonstrated good validity and reliability22.

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to statistical analyses using SPSS software version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were given as mean±standard deviation for continuous data, and as numbers and percentages (%) for categorical data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether the data conformed to a normal distribution. Categorical data was evaluated by Chi-Square test. The means of two independent samples of continuous variables were compared using the Mann Whitney U-test. A p value <0.05 was taken as the significance level.

The power of the study was determined by post hoc power analysis using the G*Power application (version 3.0.10 Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). The power (1-β) of the study was determined to be 99%, where the statistical significance of alpha was determined to be 5% and the confidence interval 95%. MIP was identified as the main result. An effect size of 1.738 was determined. Additionally, effect sizes were reported as modest (> 0.20), moderate (0.50–0.80), and large (≥ 0.80)23.

RESULTS

In total, 52 individuals aged 18-45 years were included in the study (30 post-COVID-19 individuals and 22 individuals with no history of COVID-19). The sociodemographic data of the subjects is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants

Individuals with COVID-19 infection had significantly lower measured and projected values for MIP, MEP, and 6MWT than the control group. (p < 0.05, Table 2). They also had lower sleep quality (p < 0.05, Table 2). The two groups demonstrated similar pulmonary function values (p > 0.05, Table 2).

Table 2

Comparison of pulmonary functions, respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity and sleep quality between groups

| Variables | COVID-19 individuals (n = 30) | Control group (n = 22) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (lt) | 4.78 ± 1.12 | 4.80 ± 0.86 | 0.810 |

| FVC (lt) | 5.35 ± 1.18 | 5.51 ± 1.05 | 0.663 |

| FEV1 / FVC | 89.15 ± 3.52 | 87.25 ± 5.58 | 0.415 |

| PEF (lt) | 7.22 ± 0.78 | 7.78 ± 1.12 | 0.063 |

| MIP (cmH2O) | 70.06 ± 3.34 | 77.45 ± 5.26 | 0.001* |

| MIP, % predicted | 71.21 ± 6.01 | 79.98 ± 6.33 | 0.001* |

| MEP (cmH2O) | 70.46 ± 3.83 | 78.04 ± 5.19 | 0.001* |

| MEP, % predicted | 58.20 ± 8.54 | 67.11 ± 7.54 | 0.001* |

| 6MWT | 490.16 ± 35.44 | 562.31 ± 41.62 | 0.002* |

| 6MWT %pred | 64.61 ± 5.84 | 73.56 ± 6.19 | 0.001* |

| PSQI Total (score) | 3.06 ± 1.55 | 1.81 ± 0.90 | 0.003* |

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity, and sleep quality between young people who survived COVID-19 but had not been admitted to hospital, and those who had never contracted COVID-19. The results showed that the symptomatic individuals had decreased respiratory muscle strength and exercise capacity and worse sleep quality than the latter group in a period of at least three months after a negative COVID-19 PCR test.

Previous studies on COVID-19 patients found abnormalities in pulmonary function test values such as early FEV1, FVC9,24. However, it is noteworthy that most of these individuals showed severe symptoms and had a history of hospitalization. Some studies investigating the long-term effects of the disease found pulmonary function test values to be normal or close to normal25,26. Another study conducted on young volleyball players found those with COVID-19 and those without to have similar pulmonary functions, except for respiratory muscle strength, but no abnormality in pulmonary function was found. This study also stated that inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength was more affected in players with COVID-19 compared to players without COVID-1927. In the present study, no differences in pulmonary function test values were found between the COVID-19 survivors and controls; this may be due to the fact that the individuals included in our study were young and had a mild disease.

One group of common complaints seen in COVID-19 are musculoskeletal symptoms28. Respiratory muscle involvement is thought to be more common in individuals who have had COVID-19 with musculoskeletal system involvement, with symptoms such as dyspnea and fatigue29,30. However, few studies have evaluated respiratory muscle strength, and pulmonary functions are mostly evaluated in individuals who have survived COVID-19.29 These studies were also generally conducted after hospitalization. In their study examining the long-term outcomes of COVID patients, Sirayder et al.31 reported that respiratory function, respiratory muscle strength and exercise capacity decreased even 6 months after discharge from the intensive care unit. Güneş et al.26 report a reduction in MIP and MEP, continuing for a long period, in young individuals post- COVID-19.

Similarly, our present findings indicate lower MIP and MEP values in post-COVID patients compared to controls. It was also noteworthy that the patients exhibited lower respiratory muscle strength than healthy individuals, and that the MIP and MEP values of healthy individuals were lower than expected. it is possible that this may be due to their sedentary lifestyle. Our findings suggest that respiratory muscle strength may be affected in individuals who have had COVID-19, even if the disease is mild. The long-term effects of COVID-19 are unclear.

Nevertheless, our results may be of value for guiding interventions on the subject; they may also play a critical role in understanding the systemic effects of COVID-19 and be used in developing holistic approaches targeting the recovery of physiological functions.

The underlying causes of reduced exercise capacity are not clear. Studies evaluating exercise capacity mostly focus on individuals with more severe symptoms and a history of hospitalization, and most researchers have addressed dyspnea and fatigue. A study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention32 aimed to identify patients with persistent lung failure after hospital discharge due to COVID-19 infection; the study followed up patients with a history of severe COVID-19, without previous comorbidities, after discharge from hospital. It was found that six months following the acute phase, 28% of patients with severe COVID-19 illness still demonstrated symptoms, 16% reduced pulmonary function, and 25% subpar performance on the 6-MWT. Another study by Hui et al.33 found individuals with a history of COVID-19 and no history of hospitalization to exhibit poorer exercise capacity and health status than healthy individuals.

A study by Cortes-Telles et al.34 found a mean 6MWT score of 450 m among participants who had recovered from COVID-19, while Townsend et al.35 report a mean 6MWT distance of 460 m, with the distance not being associated with disease severity. Another study based on the 6MWT found a group with a history of COVID-19 to have similar aerobic capacity to a control group. The same study reported that most of the individuals did not complain of any fatigue or shortness of breath, and did not need pulmonary rehabilitation afterward36.

It has been emphasised in the literature that functional exercise capacity plays an important role in the preparation of rehabilitation programmes37. In our study, although fatigue and shortness of breath were not observed at rest, those with a history of COVID-19 demonstrated a lower exercise capacity. It is possible that inadequate respiratory muscle strength also negatively affects exercise capacity.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many studies examined sleep disorders38,39, with some reporting that insomnia is a symptom of COVID-19. However, most of the existing studies were conducted during the pandemic and relatively few have examined sleep disturbance after COVID-19. A study investigating sleep disturbances among non-COVID-19, COVID-19 positive and post- COVID-19 patients, found that the post-COVID-19 group had a higher prevalence of insomnia with a significant deterioration in quality of life. The presence of changes in inter alia respiratory muscle strength and sleep quality associated with COVID-19 emphasises the need for specific interventions to improve the quality of life of patients and reduce the risk of long-term complications.

Another study following 781,419 young people with COVID-19 between 2020 and 2022 found only 1 % to have been hospitalized, while the rest received outpatient treatment. Despite the low hospitalization rate, 14,011 cases experienced sleep disturbance. Nine symptoms including fatigue, skeletal muscle pain and sleep disturbances associated with late COVID-19 infection were identified40. A meta-analysis of the long-term effects of COVID-19 found 24 percent of post-COVID-19 individuals experienced sleep disturbances at least three months later41.

In another study, the main complaints of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 six months after diagnosis were fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression. Sleep disturbance was observed in 26% of patients42. While sleep disturbance is a common symptom in hospitalized patients, there are very few studies examining this condition in COVID-19 outpatients. Our findings indicate individuals who survived COVID-19 but were not hospitalized still demonstrated poorer sleep quality than the non-COVID controls, despite the passage of time since the disease; in these cases, sleep disturbances may develop due to chronic fatigue and respiratory muscle weakness.

The study has some limitations. The post-COVID-19 period was not taken into account during the study. In addition, exercise capacity was evaluated at submaximal level: the use of more objective cardiovascular exercise tests to evaluate maximal exercise capacity may provide more detailed information. The results of the 6MWT may be affected by peripheral muscle strength, and we suggest that especially lower extremity muscle strength should be taken into consideration in future studies. Nevertheless, a key strength of our study is that it is one of only a few examining the effects of COVID-19 on pulmonary function and exercise capacity in individuals with mild disease. As such, it offers important data for the literature in this field.

CONCLUSIONS

By understanding the effects of COVID-19 on respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity and sleep quality is it possible to improve the quality of life and general health status of individuals in the post-COVID-19 period. We believe that it is important to include individuals who have mild COVID-19 but whose effects continue to be felt in physiotherapy programs.