INTRODUCTION

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine condition among women of childbearing age1, affecting around 4%–20%, with over 60% of patients being obese2,3. Due to the complicated endocrine features of PCOS, including an increased luteinizing hormone (LH) to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) ratio and hyperinsulinemia, many PCOS patients present with irregular menstruation4. The condition can also result in infertility, which in turn can lead to elevated infertility-related stress, emotional distress and impaired mental well-being5.

The risk of developing PCOS increases with obesity, which is associated with more severe insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and ovulatory dysfunction. Obese patients are also more at risk of metabolic syndrome, glucose intolerance, cardiovascular risk factors, and sleep apnea6.

Increased body mass index (BMI) also increase the risk of greater stress reactivity in PCOS women5, manifested as heightened salivary cortisol and α-amylase levels, both indicative of an overactive stress response7. Moreover, greater BMI exacerbates the effects of infertility-related stress on quality of life and emotional disturbance8.

Pharmacological treatments, such as metformin, oral contraceptive pills and antiandrogen agents, are commonly used in the management of PCOS. However, prolonged use of these medications can result in potential adverse metabolic and cardiovascular effects, fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis, cardiovascular and thromboembolic events, as well as hepatic toxicity, which could be fatal.9 Therefore, before any chemical treatment is attempted, the cornerstone of treatment for most overweight or obese women with PCOS, with or without infertility, is regarded as lifestyle modification through exercise and weight reduction10,11, as weight loss has been demonstrated to improve reproduction, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic markers in PCOS women12.

Aerobic exercise is recognized as a key form of physical activity that can reduce weight and enhance reproductive function in women with PCOS13, and can positively affect their psychological status and quality of life14. Maiya et al.15 found that aerobic exercises are beneficial in reducing weight in PCOS patients with obesity and infertility, leading to a decrease in cyst size, improved ovulation, and a higher chance of pregnancy. However, more research on combining aerobic exercise with lipolytic modalities is warranted to determine optimal protocols for lowering stress related to infertility and cortisol levels in obese women with PCOS.

One electro-lipolytic devices employs Ultrasound Cavitation (UC) to break down fats: this is an electric modality that uses 20-70 kHz ultrasound energy to produce unlimited tiny vacuum bubbles, which break bonds between fat cells and destroy their membranes16. Previous studies have confirmed that UC decreases visceral fat in PCOS patients, which results in lower LH/FSH ratio and testosterone levels, increased menstrual cycle regularity, higher ovulation rates, improved infertility, and increased pregnancy rates17,18. However, no empirical data or evidence-based studies have examined the impact of incorporating UC alongside aerobic exercises on menstrual regularity, gonadotropin hormone, infertility-related stress, and cortisol levels in obese women with PCOS. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine the impact of using UC on the regularity of menstruation, gonadotropin hormones, infertility-related stress, and cortisol levels in obese PCOS women when combined with aerobic exercises. The authors hypothesize that the combination of UC with aerobic exercises would improve menstrual regularity, gonadotropin hormones, infertility-related stress, and cortisol levels more than aerobic exercises alone in this group of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This study was a double-blinded, randomized, controlled study carried out in the outpatient clinic of the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University. It ran from June 2023 to November 2023.

Ethical approval statement

The Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University [No: PT REC/012/004488] gave ethical approval before the study started. It was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov [NO: NCT05880550]. The study’s protocol was explained to each participant, which gave their informed consent to take part. The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines for human research.

Recruitment and Randomization

Sixty women diagnosed with PCOS, obesity and infertility were recruited from the infertility outpatient clinic at Kasr Al Ainy Hospital, Cairo University and referred to the outpatient clinic for women’s health at the Faculty of Physical Therapy, Cairo University, Egypt. All patients were initially screened for eligibility. PCOS diagnosis followed the Rotterdam criteria, necessitating the presence of a minimum of two of the following: [1] Appearance of polycystic ovaries on transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound [2] Hyperandrogenism confirmed biochemically (testosterone > 2.0 nmol/L, free androgen index > 5.4) or clinically (hirsutism evaluated by Ferriman-Gallwey score > 8); and [3] irregular oligo/anovulatory menses (cycles < 21 or > 35 days) 19. The study enrolled women aged 20-35, with BMI above 25 kg/m² and below 35 kg/m² and Waist/hip ratio (WHR) more than 0.8820. The exclusion criteria comprised use of oral contraceptives or any fertility treatments, skin diseases that prevent the application of cavitation, history of respiratory, kidney, hepatic, or cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, cancer, endocrine disorders (hypothyroidism- hyperprolactinemia), or taking hormonal treatment within the three months before the study. In addition, patients who were smokers, alcohol drinkers, or participating in any heavy physical activity were excluded.

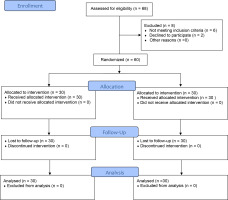

Randomization was performed via computer-generated random number tables sealed in opaque envelopes by a research assistant to reduce bias. A 1:1 allocation ratio assigned participants to group (A) or group (B). The randomization protocol was kept secure by the research assistant. The patients and investigators responsible for follow-up were blinded to the randomized allocations until the completion of final statistical analyses. After randomization, no subjects dropped out of the research (Figure 1).

Interventions

Group (A), the control group, consisted of thirty obese PCOS women who received aerobic exercise training for 50 minutes on the treadmill, five times weekly for 12 weeks. Group (B), the cavitation group, consisting of thirty obese women with PCOS, received the same aerobic exercise training programme for 12 weeks, as well as UC treatment on the abdominal area for 30 minutes, once per week for three months.

Aerobic exercise program

All women in both groups (A & B) performed aerobic exercise at a moderate intensity (i.e. 60-70% of the maximum heart rate, HRmax) for 50 minutes on an electronic treadmill (AC5000M, China) five times weekly for 12 weeks. Heart rate was monitored by a link connected to the treadmill; patients warmed up for 10 minutes (walking on the treadmill at 30-40% HRmax) followed by 30 minutes of active training, then 10 minutes cooling down (walking on the treadmill at 30-40% HRmax). Maximum heart rate (HRmax) was determined by the equation: HRmax= 220 – age. After warming up when the patient reached the target intensity (60-70% HRmax), the speed was adjusted according to the target intensity21. The researchers ensured compliance with the prescribed exercise program by the participants by tracking attendance and offering continuous guidance and supervision during each session.

Ultrasound cavitation

Together with the aerobic training, Group B received ultrasound cavitation (UC). This was performed using an INFORM 360 Degree Cryolipoysis Slimming Machine with extension cavitation head, with the following parameters: frequency 40KHz, maximum intensity 6-8 watt/cm2, continuous mode, power consumption 1000 W, power input AC (110/220) V, Item No: AU-99, made in China. The ultrasonic cavitation technique was explained briefly to all participants in Group B to reassure them and improve cooperation.

At the start of each session, the patients were told to empty their bladders to foster a calm and comfortable atmosphere during the session. Each woman was asked to assume a standing position. The abdominal region was vertically divided into equal right and left segments, extending bilaterally from a line stretching between the mid axilla above and the iliac crest below, and upward from the diaphragmatic center to the midpoint between two iliac crests below. the participants were asked to assume a supine lying relaxed position. After sterilizing the skin on the front part of the abdomen with alcohol, gel was applied as a coupling medium onto the cavitation probe head. The device was switched on, and the intensity was set at 2.5 watts/cm2. Then, the probe was moved in slow, rhythmic vertical circles over each abdominal segment for 15 minutes.

Each treatment session on the abdomen lasted 30 minutes22. The probe was then placed at the lymphatic drainage site of the treated areas for 10 minutes. This facilitated the opening of the main lymph nodes, promoting the flow and removal of excess fluids, which allowed fat waste to be naturally eliminated. After finishing the UC, the skin was cleaned with cotton. The total treatment duration per session was 40 minutes on the abdominal area, applied once a week for 12 weeks20.

Outcome measures

The same assessor evaluated the measures before and after the intervention. This assessor was not involved in the treatments and was blind to the grouping of each patient.

Body mass index measurement

Each participant was measured by a weight-height scale at baseline, with only weight reassessed post-treatment. All participants work light clothing, without shoes, during measurement. BMI was calculated using the standard equation: BMI = Weight (kg) / Height squared (m)2.

Waist/Hip ratio measurement

Waist circumference was measured by a tape measure around the midpoint between the iliac crests and lowest rib margins; the measurement was taken with the patient standing with both feet together, at the end of a typical exhale. Hip circumference was measured at the level of the greater trochanter. Then, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) for each woman was calculated by dividing waist circumference by hip circumference23. Both circumferences were measured for all women in both the control and study groups at baseline and post-treatment.

Menstrual regularity assessment

Mean cycle length was calculated based on data collected by the participant using a menstrual calendar to detect the first day of each menstrual cycle along the treatment time (12 weeks). A regular menstrual period was defined as a cycle length lasting 21 to 35 days24.

Hormonal profile (LH- FSH – LH /FSH ratio) measurement

A blood sample of 5 cm was collected from the antecubital vein for each patient in both groups to determine gonadotropin hormone levels (LH, FSH, and LH/FSH ratio). Baseline LH and FSH were measures in the central lab utilizing a Flash 3200 Fully Automated (FSH-Flash and LH-Flash) on menstrual cycle day three. LH/FSH ratios were calculated using the formula: baseline LH (mIU/mL)/FSH (mIU/mL) 25.

Infertility-related stress measurement

It was assessed using the Infertility-Related Stress Scale (IRSS). This is a concise, reliable, and validated tool that facilitates quick screening for the impact of infertility on intrapersonal and interpersonal life domains. The IRSS consists of 12 items rated from 1 (“no stress”) to 7 (“high stress”), covering intrapersonal (leisure/enjoyment, global life satisfaction, perceived mental and physical health, sexual pleasure, and marital satisfaction) and interpersonal (work performance and the relational contexts of relatives/family of origin, in-laws, friends, colleagues/acquaintances, and neighbours) aspects. The intrapersonal domain score is calculated by summing items 1, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 12, and the interpersonal domain score by items 2, 3, 7, 8, 10, and 11. Adding up all the items results in the total score on the twelve-item scale26.

Plasma cortisol level measurement

Blood samples (5 mL) were taken following an overnight fast and 30 minutes of morning rest, i.e. between 7 and 9 AM. Serum was separated by 6-minute 3500 rpm centrifugation, and cortisol was assayed promptly using ATELICA kits, FLASH 180027.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculation was performed as an a priori-type power analysis for mixed-design MANOVA using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). All the requirements for sample size calculation were determined. The primary outcome was the LH/FSH ratio. As suggested by Cohen (1994), an effect size (cohen f (v)) of 0.4 was selected and inserted in the G power software. The alpha error of probability (α) was adjusted at 0.05, and the power of the study (1-β err prob) was adjusted at 0.8. The software calculated the minimum sample size to be 52 individuals. Considering 10% to 20% of sample dropout and ensuring a good power of significance, the total sample size was increased to 60 (30 in each group). Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram of the participants throughout the study. The participants did not report any negative effects or complaints during or after the treatment period.

Before the statistical analysis was performed, data exploration was carried out to determine a suitable statistical parametric or non-parametric test. The Shapiro-Wilk test found the data to be normally distributed (p < 0.05(, which was confirmed by frequency distribution curve and boxplots, which also showed normally-distributed data with normal skewness and kurtosis. Therefore, parametric statistics were performed using two-way mixed design MANOVA to compare the BMI, WHR, LH, FSH, LH/FSH ratio, interpersonal domain, intrapersonal domain, and cortisol level between the two tested groups (A and B) before and after treatment. Concerning the regularity of menstruation, the non-parametric McNemar test was applied for each tested group to test the significance of regularity change between pre-treatment and post-treatment. SPSS version 28 for Windows was used to carry out all statistical analyses. p < 0.05 was chosen as the significance level for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

Sixty-eight patients were initially screened for eligibility. Sixty were accepted into the experiment and randomized into two groups (Figure 1). One-way between-subject MANOVA did not reveal any significant difference in patient demographic data, including age, weight, height, and BMI, between groups A and B (p > 0.05), indicating that the two tested groups are homogeneous (Table 1).

Table 1

One-way between subject MANOVA for the demographic data of the two tested groups

No significant differences in the mean values of any of the measured outcomes were identified between the two tested groups (A and B) at the pre-test point (p > 0.05). In both tested groups, the post-test values of the following parameters were found to be significantly improved compared with the pre-test values: mean BMI, WHR, LH, LH/FSH ratio, interpersonal domain, and intrapersonal domain of infertility-related scale and cortisol level (p < 0.05; two-way mixed design MANOVA). The following respective improvements were found in Group A: 7.67%, 6.52%, 17.22%, 17.87%, 19.90%, 17.60% and 28.29%; and the following respective improvements were found in Group B: 15.86%, 12.1%, 35.45%, 34.47%, 34.30%, 31.30% and 51.11%. However, no significant change in mean FSH value was found between post-test and pre-test in either group A or B (p > 0.05): the percentage of improvement of FSH in was 2.8% in Group A and 3.4% in Group B (Table 2).

Table 2

Two-way mixed design MANOVA of outcome measures

| Outcome measures | Group | Pre-treatment | Post treatment | Group A vs. Group B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | MD (95% CI) | p value | Pre-p value | Post p value | MD (95% CI) | ||

| BMI | Group A | 32.86 ± 1.5 | 30.34 ± 1.47 | 2.52 (2.23 , 2.80) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.095 | p = 0.000* | 2.17 (1.40 , 2.96) |

| Group B | 33.48 ± 1.29 | 28.17 ± 1.53 | 5.31 (5.03 , 5.60) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| WHR | Group A | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 0.06 (0.042 ,0.063) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.212 | p = 0.000* | 0.06 (0.05 , 0.08) |

| Group B | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.11 (0.10 , 0.12) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| LH | Group A | 12.95 ± 3.28 | 10.72 ± 2.44 | 2.23 (1.48 , 2.97) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.414 | p = 0.000* | 2.8 (1.75 , 3.84) |

| Group B | 12.27 ± 3.07 | 7.92 ± 1.49 | 4.35 (3.61 , 5.08) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| FSH | Group A | 5.65 ± 1.37 | 5.49 ± 0.68 | 0.16 (-0.19 , 0.52) | p = 0.362 | p = 0.398 | p = 0.096 | 0.32 (-0.06, 0.70) |

| Group B | 5.35 ± 1.36 | 5.17 ± 0.77 | 0.18 (-0.18 , 0.54) | p = 0.316 | ||||

| LH/FSH ratio | Group A | 2.35 ± 0.33 | 1.93 ± 0.38 | 0.42 (0.16 , 0.70) | p = 0.002* | p = 0.962 | p = 0.000* | 0.39 (0.23 , 0.54) |

| Group B | 2.35 ± 1.02 | 1.54 ± 1.88 | 0.81 (0.54 , 1.07) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| Interpersonal domain | Group A | 34.67 ± 3.46 | 27.77 ± 2.97 | 6.90 (5.87, 7.93) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.511 | p = 0.000* | 4.57 (2.87 , 6.27) |

| Group B | 35.31 ± 4.00 | 23.20 ± 3.99 | 12.11 (11.07 , 13.14) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| Intrapersonal domain | Group A | 33.20 ± 3.27 | 27.36 ± 3.21 | 5.84 ( 4.51 , 7.16) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.822 | p = 0.000* | 4.69 (3.06 , 6.33) |

| Group B | 33.00 ± 3.59 | 22.67 ± 3.11 | 10.33 (9.00 , 11.66) | p = 0.000* | ||||

| Cortisol level | Group A | 13.08 ± 2.69 | 9.38 ± 2.12 | 3.70 (3.08 , 4.31) | p = 0.000* | p = 0.501 | p = 0.000* | 2.76 (1.82 , 3.71) |

| Group B | 13.54 ± 2.57 | 6.62 ± 1.49 | 6.92 (6.30 , 7.53) | p = 0.000* | ||||

Regarding intergroup comparisons, the study group (Group B) demonstrated a significant reduction in the following compared to the control group (Group A): mean BMI by mean difference (MD) (2.17 ; 95% CI [1.40:2.96], p = 0.000), WHR (0.06 ; 95% CI [0.05:0.08], p = 0.000), LH (2.8 ; 95% CI [1.75:3.84], p = 0.000), LH/FSH ratio (0.39 ; 95% CI [0.23:0.54], p = 0.000), Interpersonal domain of IRSS (4.57 ; 95% CI [2.87:6.27], p = 0.000), Intrapersonal domain of IRSS (2.76 ; 95% CI [1.82:3.71], p = 0.000) and cortisol levels (2.76; 95% CI [1.82:3.71], p = 0.000), Meanwhile, no significant differences were found in post-test mean FSH level between Group A and Group B (0.32 ; 95% CI [-0.06: 0.70], p =0.096) (Table 2).

No significant change in menstruation regularity was noted after receiving treatment compared with pre-treatment status in groups A or B (p > 0.05; McNemar test). As presented in Table 3, only three patients in Group A showed an insignificant change from irregular menstruation (before treatment) to a regular status (after treatment), while 24 patients remained irregular before and after treatment (p > 0.05). Regarding group B, only five patients showed an insignificant change from irregular to regular status after treatment, while 21 patients remained irregular before and after treatment (p > 0.05).

Table 3

McNemar test crosstabs of menstruation regularity in patients with PCOS

DISCUSSION

PCOS is frequently associated with obesity and infertility, both of which may exacerbate the adverse impact of stress6. The current study aimed to determine how adding ultrasonic cavitation (UC) to aerobic exercise can influence menstrual regularity, gonadotropin hormones, infertility-related stress, and cortisol levels in obese PCO patients who were infertile.

Intra-group comparisons revealed statistically significant improvements post-treatment compared to pre-treatment in all measured parameters (BMI, WHR, LH, LH/FSH ratio, infertility-related stress, and cortisol) at p < 0.05, except for FSH levels and menstrual regularity (p > 0.05). Regarding inter-group comparisons, the cavitation group exhibited significantly more significant improvements post-treatment in BMI, WHR, LH, LH/FSH ratio, infertility-related stress, and cortisol levels compared to the control group (p < 0.05). However, the intergroup differences in FSH levels post-treatment remained insignificant (p > 0.05).

Anthropometric measurements

In the control group, significant reductions in BMI and WHR were noted, which reflected the positive impact of 12-week aerobic exercise on reducing the anthropometric measurements. In the control group, the mean change (pre- to post-treatment) in BMI was 2.52 points (7.67% improvement) and WHR was 0.06 points (6.52% improvement). These improvements are considered clinically significant in this population, as it exceeds the Minimal Clinical Important Difference (MCID) of 5-10% reduction in body weight28. This result was consistent with Abazar et al.29, who showed that anthropometric measurements, including BMI and WHR, decreased significantly following a 12-week aerobic exercise program. The reductions in anthropometric measurements may result from the breakdown of body adipose tissues through the process of lipolysis30.

Regarding the cavitation group, the significant intragroup and intergroup reductions in BMI and WHR achieved with a combination of aerobic training and cavitation highlight the beneficial impact of this integrated regimen for improving anthropometrics in obese women with PCOS. The mean change (pre- to post-treatment) for BMI was 6.31 points (15.86%) and WHR was 0.11 points (12.1% improvement); again, this is considered clinically significant as it exceeds the MCID value20. These findings are supported by Abdelhamid et al.31, who observed greater effectiveness in reducing weight, BMI, and WHR among female adolescents when combining abdominal UC with aerobic exercises and a low-calorie diet. Additionally, Ascher32 postulates that UC is a potent, non-invasive method for decreasing body fat and sculpting contours.

The favourable effects of cavitation can be attributed to its non-destructive thermal heating of adipose tissue. This thermal heating accelerates natural lipolysis processes and breaks down the fat cell phospholipid membrane, resulting in an approximate one-inch reduction in the treated area16. This is consistent with prior evidence by Boshra et al.33 , who found weight loss to occur as a consequence of fat mass depletion accelerated by targeted ultrasound, and that this activates lipoprotein lipase and facilitates the breakdown of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol.

Menstrual regularity and levels of gonadotropin hormones

Significant differences in mean LH and LH/FSH ratio were observed between pre- and post- intervention in the control group: these being 2.23IU/L (LH) and 0.42 units (LH/FSH) (p-value < 0.05), suggesting that aerobic exercises had an effect on LH and LH/FSH ratio. The current findings align with Gilani et al.34 , who discovered that aerobic exercises led to a significant reduction in LH without affecting FSH. The observation that both LH and LH:FSH ratio fell in the present study might be linked to the inhibitory impact of exercise stress and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation on female reproductive function. Exercise stimulates growth hormone release, suppressing gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus. Exercise also stimulates the release of glucocorticoids, which stop the pituitary from releasing the LH and cause the ovaries to release progesterone and estrogen; consequently, aerobic exercise may reduce LH levels. Research also indicates moderate and high-intensity training induces greater parasympathetic activation and less sympathetic activity. As a result, it is advised that women with PCOS engage in regular exercise34,35.

In the cavitation group, significant differences (pre- to post-intervention) were noted for mean LH (4.35 IU/L ) and LH/FSH ratio (0.81 units; p-value < 0.05), suggesting that the intervention influenced LH and LH/FSH ratio. The hormonal improvements observed in the cavitation group align with Mekawy and Omar18, who reported that obese women with PCOS showed greater improvements in reproductive hormone levels when exercise and a low-calorie diet was supplemented with UC. The enhanced effects of cavitation may be attributable to its ability to disrupt fat cell membranes, resulting in the breakdown of fat cells and accelerated lipolysis, resulting in enhanced hormonal balance and reduced LH/FSH ratios in obese PCO women.

The improvements in hormone levels noted in both groups might be linked to the significant reduction in anthropometric measurements. A 5-10% reduction from initial body weight is a beneficial strategy for restoring reproductive, metabolic, and hormonal health in PCOS patients who are overweight36.

Although aerobic exercise and cavitation significantly improved the LH and LH/ FSH ratio, no significant changes were noted in FSH or menstrual regularity. It is possible that the 12-week treatment period may not be sufficient to fully normalize the complex hormonal dysregulation observed in PCOS, which disrupts ovarian function and menstrual regularity. More prolonged therapy may be necessary to achieve significant changes.

Infertility-related stress and cortisol levels

Given the absence of earlier research exploring the effects of aerobic exercise or cavitation on infertility-related stress, the significant improvements observed in both groups provide novel evidence for the psychological benefits of these interventions. The respective mean differences in the interpersonal and intrapersonal domains of infertility stress scale (pre- to post-treatment) were found to be 6.90 and 5.84 points for Group A, and 12.11 and 10.33 points for Group B; these represent, respectively, 19.90%, 17.60%, 34.30% and 31.30% improvements in stress levels after intervention (p-value < 0.05), suggesting that the intervention had an effect on both domains of IRSS. The current findings conceptually align with Nikolovska37, who stated that cellulite and fat accumulation negatively impact self-esteem in women, with detrimental effects on motivation, activity, mood, and performance. Optimizing weight and reducing cellulite positively impacts mood, performance, self-esteem, and general psycho-emotional state.

Regarding mean cortisol level, significant differences (pre- to post-treatment) were found in both groups: 3.70 points for Group A (28.29% improvement) and 6.92 points for Group B (51.11% improvement) (p-value < 0.05). This suggests that the intervention had an effect on the cortisol level. The reduction in cortisol levels with aerobic training aligns with de Souza et al. 38, who demonstrated significant decreases in cortisol across four days of moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise. Similarly, De Nys et al.39 found that physical activity programs can improve cortisol levels, which may benefit those with chronic conditions. The cortisol-lowering effects of exercise may be attributable to its modulating effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which represents a core regulator of the response to stress40. The greater cortisol reduction observed in the cavitation group compared to the control group aligns with previous evidence linking decreased cortisol concentrations to weight loss41. These results support theories that obesity itself, rather than PCOS specifically, is the primary driver of adrenal stimulation and cortisol elevation42. The enhanced cortisol-lowering effect of cavitation may stem from its ability to reduce visceral fat deposits selectively. Increased visceral adiposity has been associated with higher cortisol production43.

Strengths and Limitations

The present research has certain valuable strengths. It represents the first double-blinded randomized study assessing the impacts of adding UC to aerobic exercise on infertility-related stress and cortisol levels in obese PCO patients with infertility. Another key strength is its accurate measurement of hormonal profile, cortisol, and stress-related fertility; this provides a clearer view of the changes, and may contribute to crucial insights. Moreover, the required participant sample size was carefully predetermined, thus improving the reliability and validity of the results.

However, despite these strengths, this study has some limitations. The participants were only followed for 12 weeks, and a longer follow-up is required to ascertain if the effects are sustained over time. In addition, the sample size of participants was rather small. Future clinical studies with an increased sample size could provide a more accurate understanding of the effects of UC on PCOS.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings indicate that adding UC to aerobic exercise for PCOS patients with abdominal obesity resulted in a more considerable decrease in BMI and WHR compared to aerobic exercise alone. The addition of UC was also linked to a greater improvement in hormonal abnormalities and decreased stress levels compared to aerobic training.